Grief is often associated with the death of a person or a separation. However, it is also a faithful companion to many relatives of people with dementia. But why is that so?

Grief is a deep feeling of loss that occurs when someone or something dear is lost," says Anja Schmidt-Ott, a grief counselor in Wuppertal. In the world of dementia, grief means the loss of both person and personality as families knew them. They look back on the past, while also mourning the present loss and the shared future.

Relatives of people with dementia experience the pain of loss in everyday life as well. They repeatedly witness abilities and skills disappearing and routines and rituals coming to an end. The relationship with the person also changes. "With the illness, a part of one's own identity is lost, as well as the shared history that connects you with the person," explains Anja Schmidt-Ott, who works as a family coach at Desideria Care, supporting relatives of people with dementia.

Grief in Dementia – Invisible and Unseen

But what makes grief in dementia so special? Experts speak of "invisible" or "unseen" grief. "It is invisible because it is often not perceived as such by the surroundings and even by the relatives themselves," says the expert. After all, the "mourned" person is still alive – and in our minds, grief is closely linked to death.

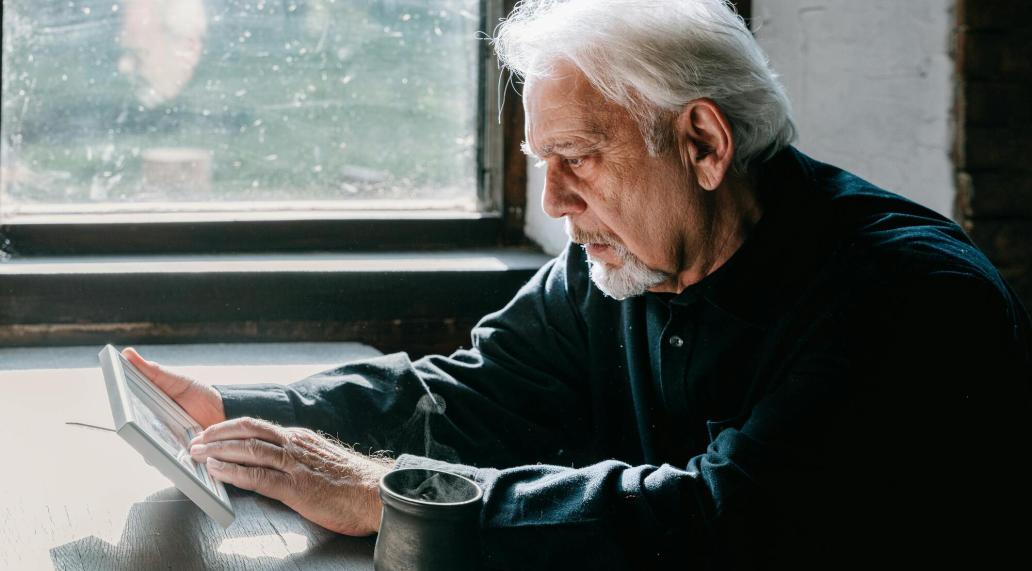

This invisibility of grief often makes it difficult for relatives. They feel left alone with their emerging feelings and often cannot properly understand or communicate them. A certain speechlessness results, and often also a feeling of loneliness.

A long process of mourning with many emotions

Family members who accompany people with dementia go through a long process of farewells. Time and again, it is necessary to say goodbye to small and big things, to shared routines and activities. It is like a labyrinth where one repeatedly traverses similar fields: from "functioning" and "surviving" to "understanding" and "accepting".

Almost everyone is in survival and functioning mode at the beginning of grief," says Anja Schmidt-Ott. This is also the case after a dementia diagnosis. However, as the disease progresses, caregiving relatives must take on more and more tasks, organize care, coordinate doctor visits, and accompany their loved ones. In everyday life, there is usually little time left to grieve and deal with the various emotions—such as sadness, guilt, shame, and anger.

Giving Space to Feelings

Many relatives suppress their emotions, especially negative ones like anger. However, grief counselor Anja Schmidt-Ott considers them normal. She says: "The anger comes from grief, from fear, from worry, from being overwhelmed and helpless – and what else is behind that if not love?" Ultimately, anger is an expression of love and is quite normal within certain limits.

What can relatives do? Anja Schmidt-Ott emphasizes the importance of accepting one's own grief. It is important to recognize that you are in an exceptional situation and that it requires a lot of strength and energy. "It is helpful to take time out and do something good for yourself. Grief groups and training can also be supportive," explains the expert. These groups not only provide space to process grief, but relatives also learn strategies to strengthen their own resilience.

Better than pushing away intense feelings is giving them space. "In the long run, suppressing grief can be unhealthy," says Anja Schmidt-Ott. It's like a tennis ball that you push underwater – eventually, it resurfaces with all the suppressed emotions. "When some people get stuck in their grief, depression can develop, or the grief may find other ways to manifest," says the grief counselor.

Coping Well with Grief

There are various ways to cope with grief, and not all of them are helpful in the long run. Dealing well with emerging emotions can be achieved through conversations, but also physical activity and sports benefit many people. Writing a diary or journal, or expressing oneself artistically through dancing, painting, singing, or playing music can help. It's important that they are given space.

Often, family members also hold back their own feelings to avoid overwhelming people with dementia. During the course of a dementia illness, the relationship often changes, and it becomes increasingly difficult to stay connected with words. Relatives do not express their feelings, but people with dementia often sense that something stands between them – and this can be unsettling and cause agitation. It's no coincidence that the saying goes: "The heart does not become demented." Even people with advanced dementia have a keen sense for emotions.

Holding back one's own emotions can lead to growing distance in the relationship," explains Anja Schmidt-Ott. Often, it results in a vicious cycle because family members continue to hold back their feelings, which further strains the relationship. At home, it also helps the person with dementia if relatives become clear about their feelings, learn to deal with them, and find a good way to cope with the grief.

Working together makes it easier

It is often a long and difficult journey for relatives of people with dementia. This also includes saying goodbye again and again. But it is also a journey that one does not have to take alone. Grief is a constant companion, sometimes taking up more space, sometimes less. Yet, it is important to know that you are not alone with your feelings. It is often easier together, including when grieving. Relatives can find support in family or self-help groups, family training such as those offered by the Alzheimer Society, and in conversations with other relatives.

Family members can also discuss with care consultants, such as those from famPLUS, to explore possible support options.

From Peggy Elfmann

Sources:

Interview with Anja Schmitt-Ott https://www.desideria.org/ueber-desideria/unsere-coaches/dr-anja-schmidt-ott

https://alzheimerundwir.com/grief-anja/